Try not to be too surprised, but the sixth installment in the Harry Potter series is not good. (Oh hell, you've probably already seen it anyway.) The pit-falls are many, and before I get more in-depth I'll just say that the dialogue is for the most part pretty stilted, and, let's face it, these poor kids can't really act. (Daniel Radcliffe performed well enough in his Equus stint, but when it comes to portraying normal human interaction he still misses the mark. And I say "kids," though actually they're all now in or nearing their twenties.)

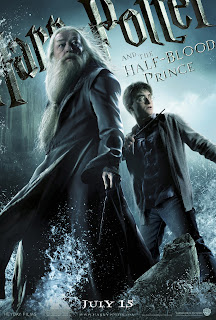

Try not to be too surprised, but the sixth installment in the Harry Potter series is not good. (Oh hell, you've probably already seen it anyway.) The pit-falls are many, and before I get more in-depth I'll just say that the dialogue is for the most part pretty stilted, and, let's face it, these poor kids can't really act. (Daniel Radcliffe performed well enough in his Equus stint, but when it comes to portraying normal human interaction he still misses the mark. And I say "kids," though actually they're all now in or nearing their twenties.)It starts off well enough: a beautifully rendered sequence of furious, smoky forms hurtling through the streets of London, Muggles looking on in pitiable nescience, and culminating with frightening intensity in an attack on the Millennium Footbridge — but immediately, the film fails to capitalize on its elegantly unsettling atmosphere by thrusting us into a jarringly unrelated space. The jumping continues as we're fed event after event, each giving us just enough information to see that it's probably relevant, but not so much as to enrich the experience. David Yates, who also directed the Order of the Phoenix, treats almost every scene with the same contemplative slowness, with the result that even those actions you know must be exciting plod on in languorous dispassion. (He seems also to have had an aversion to the immobile; for all the gently drifting tracking, crabbing, tilting, panning shots, this picture may as well have been filmed in boats.)

The larger problem with Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince is its failure to take responsibility for itself. As an audience, we are expected to know what's going on whether it's explained to us or not. Little or no effort is made to connect events or introduce characters, or to impart the gravity of a situation. It's understood that we've all read the book, that the real reason we're there is to see what we've only until now imagined. We already know how to feel. . . . This film is nothing but an illustration of its progenitor. Without the strength to stand, it leans for support; it lacks the heart to propel itself. A similar disservice might be the stage production of The Lion King . . . without music.

But, the visuals are awesome, so we keep coming back.

This is the still larger problem with the American movie audience. Our demands are too shallow. Too many fans of J.K. Rowling content themselves with whatever they're given, satisfied by the mere sight of the story. I spoke to one such satisfied customer who said, Well, I don't really have an expectation that these will be great movies. Another fan, this one angry, though I think he still enjoyed the film, complained only that there is a scene which "is not in the book!" Yet another, observing more than complaining, placed the blame for the movie's impotence on Rowling herself, saying, She's not quite Oscar Wilde when is comes to writing sexual tension.

!

A movie is not the book. If it tries to be, it will fall short: merely, as I have said, an illustration. A film must be thought of as separate from its source. Having taken a text or any other material as its starting point, it should be free to evolve and function independently. Without such freedom, Ed Wood may never have met Orson Welles, Jiminy Cricket would have been crushed before he even got on the road, and can you imagine a Jurassic Park with all the trouble in Jurassic Park? (There are limits to how long people will sit.) Of course, Harry wouldn't have found himself flirting with a waitress in a tube station either, but the independence of the Half-Blood Prince serves little purpose.

What we need is to stop being cowed by the wow! of visual effects, and demand movies that stand on their own.

What the remaining two Harry Potter films need, is Alfonso Cuarón. :(